THE INITIAL CASING

Bands of green aurora above the northeast horizon were warming up. A bear working his way through twisted and

stunted silhouettes of a black spruce bog approached the small cabin. He sampled air currents, rich and spicy, drifting from the cabin and drooled. The grizzly lurked, listening, smelling, scratching, moving, waiting, salivating. It was a wary approach for a beast who reigned the night. Satisfied, the grizzly circled the cabin on a small wooden walkway, smelling, pushing, grunting, testing. At the back of the cabin, odors were particularly strong. Half standing, he placed his huge paws on either side of the 2-foot window. He started with a gentle shove. The wall creaked and popped. The window, frame and all, fell into the cabin. The grizzly’s massive head and neck filled the window opening, and he got a real good whiff. He liked the sound of cans hitting the floor. He had struck the mother lode, the well stocked pantry of Deirdre Higgins’ bush cabin.

Then as the aurora danced, the great grizzly stepped off the walkway, disappearing into the night.

THE NEW PIONEERS OF THE LAST FRONTIER

Deirdre came here in 1986 after hearing the call of free land. She was one of those hardy and perhaps naive breed of

new pioneers who staked and filed on 5 acres of wilderness along the northern border of Wrangell/St. Elias National

Park and Preserve. It was the final land giveaway, the last curtain call in the U.S. Homestead Act. Many of the new homesteaders dreamed of a subsistence lifestyle, but in reality, few would find success living off the land. Game and fur were scarce in this absolute wilderness, with little room for new trappers. Established trappers already had the whole state of Alaska divvied up among themselves and didn’t take kindly to trespassers, trapper or otherwise. Old-school trapper and guide Doc Taylor’s advice to Steve Hobbs, a homesteader with potential, was, “You can have what you can take.”

The “simpler” life they had come in search of would never mean “easier.” Luxuries were few, but there

was time for grayling fishing in nearby Natat Creek. On this particular day, Deirdre had dinner in mind as she

crept through the brush toward her favorite hole, careful not to spook a small school of grayling. About to cast her lure into the greenish yellow stream, she glanced down. The tracks of a big grizzly pressed deep into the muddy bank slowly materialized. Grayling forgotten, Deirdre rushed up the creek to Glen Helman’s homestead. Flushing with the excitement of her first “bear encounter,” she quickly told Glen, “There’s been a bear down at my fishing hole,” to which Glen casually replied, “Deirdre, it isn’t your fishing hole.” Deirdre didn’t have bear problems. But the summer of 2001 found her small bush cabin vacant for the first time. She had gone outside for the first time in fifteen years. I wasn’t surprised to see the big grizzly prints in the mud as I hiked the trail to check on the cabin belonging to Marie and Jim Morris, Deirdre’s daughter and son-in-law. Easily recognizable, this bear left the biggest tracks in the settlement. But, I had never met the grizzly that made them. Few had.

The grass had grown tall in Jim and Marie’s yard during this summer, nearly obscuring their enviable fleet of snowmobiles. But what I saw next stopped me in my tracks. The door was open into their arctic entry and pantry and had taken a direct hit. Fearing I’d blundered into the scene of a crime in progress, I searched the thick, young spruce for his dark form. I remember wishing I’d brought my bear spray, no, make that my .338 Winchester magnum. No, I wish that Jim were here to clean up his own damn mess. Bear trails, spoking out from the pantry into the trees, were littered with ripped, smashed and crunched boxes of cake mixes, spices, and a Crisco can. There were other cans, punctured, tasted, rejected. Apparently anything the bear wanted to give a try was hauled out to the yard. Empty packages of graham crackers, chocolate chips, and marshmallows lay close to the door. He seemed to like s’mores!

Marie’s mom, Deirdre, lives just 100 yards down the trail. I checked her place next and discovered that the bear

had pushed her pantry window into the cabin, where it lay unbroken on a sofa. I knew my kids would want to see all

the havoc the bear had caused, so with them in tow, I later returned to clean up and nail a piece of plywood over

Deirdre’s window opening. Two days later, we were back to again clean up Jim and Marie’s yard and arctic entry. We salvaged what we could, filling up a couple of large boxes. Everything else went into garbage bags. We packed everything to go. Before leaving, we built a decoy using a jacket, a canoe paddle, and my hat. We left it guarding the door.

MORE GRIZZLY DISCOVERIES

At Deirdre’s cabin, the returning bear had this time pushed both doors open, breaking the door jambs. A path of

carnage led from the yard into Deirdre’s pantry. He had certainly gotten over his shyness. Why had the grizzly suddenly left Deirdre’s pantry after pushing in the window on his earlier visit? Had he lost his nerve? Already had a full stomach? , thinking about going straight? Or was this the Modus Operandi of a career criminal, a bear with enough Slana street smarts to still be wearing his 10-foot hide? In the yard, a large Crisco can had been licked clean. Two jars of homemade chili had been carried outside too, their tops bitten off and the contents partially licked out. He had eaten everything—glass and all! An entire case of Tones Spicy Spaghetti Seasoning littered the cabin entrance. A couple of bottles had been spilled and tracked in and out of the cabin. It reeked of Spicy Spaghetti. A small can of cat food, punctured by some very big canines, oddly, was completely empty. He’d sucked out the contents! At Glen Helman’s place, the kitchen was in shambles. Glen had passed away the year before, but the kitchen had never been cleaned out. The kitchen cupboards still stored enough food to keep the grizzly bear interested. The bear had broken windows and doors and tossed the full sized refrigerator

around like an empty box. Glen’s cat Sammie was living alone now. Sometimes as I approached Glen’s place, I

would see him run up the back steps, climb the broken screen door and disappear into the attic. Did Sammie hide

up there, too, when the grizzly came visiting? Sammie maintained a scent station in Deirdre’s yard. The small scrape, scented with urine and droppings, laid claim to the homestead. Sammie did apparently have to share the

spoils with that big grizzly with the sweet tooth, though.

SETTING THE TRAP …

The decoy at Jim and Marie’s seemed to be working, but Deirdre’s cabin was hit twice more in a week. Her yard was getting really messy, at about the same rate as her pantry was being cleaned out. Reaching down I picked up a couple small decorative glass dishes out of the tall, yellowing grass. They were about half full of bear spit. Inside, more glass dishes were displayed on the kitchen table, filled with candy. I stood there next to the kitchen table, trying to picture the big grizzly sneaking in, carefully picking up delicate dishes of candy, and tip toeing outside with his treasure.

That’s when it hit me. Not in a subtle way, but with the kind Deirdre’s grizzly would use to knock the brains out of a bull moose. In my mind’s eye, I could visualize a great photograph! It just hadn’t been taken yet.

Back home I readied my gear. Let’s see: Nikon F4, maybe a 24-mm lens, 400 ISO film, tripod, flash, oh yeah,

batteries, .338 mag., Shutter Beam. Ready to roll, I returned to the inside of Deirdre’s kitchen, where I studied the layout. With the Shutter Beam against the south wall, I aimed its infra-red beam over the kitchen table toward a small reflector. Turn on Beam Align. Align. Turn off Beam Align. Plug camera cord to Shutter Beam. Turn on camera. Adjust settings. Look up to see if grizzly is standing in the doorway. Focus lens. Attach electronic

flash. Turn flash on. Put in new batteries. Turn on flash. Adjust settings. Look out window to see if grizzly

bear is coming. Test trigger point and camera operation. Move table 4 inches back. Grab rifle. Make sure grizzly isn’t in the yard. Close both doors. Sprinkle Tones Spicy Spaghetti Seasoning in front of the door. Go home. Wait and worry.

THE BEAR FACTS AND OTHER TAILS

Bear problems were not new around the settlement. All the abandoned homesteader shacks had long since had their

doors broke down and the food caches raided. Sometimes the four-pawed vandal just came and went through the door. Just as likely, he would enter or leave through a large window or, if it suited him, right through the wall. It was all the same to the big, shy grizzly. His fame grew. One homesteader, tired of returning home after a season

of work and finding the front door knocked down and the kitchen looking like a group of rock stars had “partied hard,” came up with a plan. So when work finally rolled around again, Eric hauled all the dry goods from the kitchen and left them inside his spare vehicle, a solid, Chevy Capri. Once back at home he found the old Capri looking like the loser in a demolition derby. Windows were smashed, the trunk lid ripped off, the doors and roof caved in. After that, the bear seemed to enjoy rearing up with both front paws to cave in doors and tailgates.

It was bears, of course, that caused the most problems, but then, weren’t they just taking advantage of homesteader

mistakes? We share our wilderness neighborhood with other wild residents too, but never in complete harmony. Griz and Melonie lived on the outlying edge of the Slana settlement about half a mile from anybody. Spending the

first winter as a homestead underground earned him the name Griz. Caribou were wintering nearby,

shoveling snow with their big hooves uncovered lichens and grass. Griz and Melonie had two young husky crosses that winter. One night the wolves were in the neighborhood. When they set to howling, one dog whined and pawed at the front door, desperate to be let in. The other, seduced by the call of the wild, went off to play.

The dog was still gone next morning so Griz went looking. He found his dog out there all right, but not much of it.

Just fur, bloodstained snow, and a few large cracked bones.

SMILE, YOU’RE ON QUINTON’S CAMERA

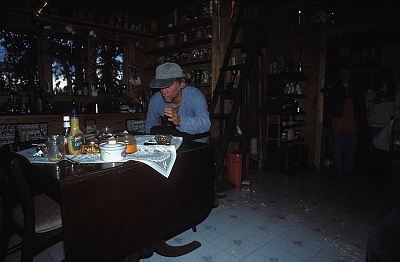

My flash batteries would not last a full 24 hours, so every morning and evening I made my way down the forest trail to

Deirdre’s cabin. I moved slowly, watching and listening for sounds that might betray the grizzly’s presence at the cabin. Every

morning I feared he wouldn’t come back while simultaneously fearing that he would.

On the third morning, there were fresh tracks! He had come back. The cabin door was open, and my heart pounded.

As I flipped the safety off, I feared I had missed the picture even more than I feared he might still be here. There was a big

muddy track smack in the middle of both doors. Inside, nothing seemed to have been moved at all. I walked into the kitchen and

through the beam, triggering the camera. The flash didn’t fire. But had the film advanced during the night? The camera frame counter

said it all—two frames had been exposed. I quickly rewound the film and reloaded the camera. Then I noticed the scratches in the

linoleum tiles. Like tracks in the snow, these marks told the story. The grizzly bear had walked right up to the table, the camera

clicked, the flash fired, and he bolted out the door for parts unknown. I changed the batteries and quickly left. For 2 more weeks I

kept the camera system operational in Deirdre’s cabin and waited for my roll of film to return from the lab. The bear didn’t return. But

accounts of destruction from the far side of Mount Suslo told of his whereabouts. I had rarely been so anxious checking the results of a

box of slides. The roll contained some two dozen pictures of Deirdre’s kitchen table. Most were test shots I’d triggered each time I

returned to change flash batteries, just to make sure the system was working. But there was one slide identical to all the rest, except

for one thing—it was the one I’d imagined before I set up the camera! Looming big and unbelievable, Deirdre’s grizzly stood at the

kitchen table deciding which dish of candy to steal.

THE BEAR END

Unable to break bad habits or forget old appetites, the grizzly was back raiding Deirdre’s cabin again in the fall of 2002. And again, I set up my photographic ambush but the grizzly never came back. A moose hunter, returning for a load of meat a few miles from Deirdre’s cabin, found the big grizzly in possession of his kill and shot him.

Meanwhile, after surviving nearly 2 years on a diet of voles and shrews, Sammie the cat finally adopted Jim and

Marie. And in late August of 2005, Deirdre’s vacant cabin was once more being raided by a grizzly bear.